One of my good friends is the international marketing director for a California winery. He met his wife during one his frequent visits to Japan.

A few weeks ago a large envelope arrived from their home in California. It contained one of my friend’s meticulously sequenced and packaged mix CDs, as well as the usual assortment of fun stuff from his trips around the world – museum postcards and posters, ads featuring hilarious English malapropisms, handbills for rock and roll shows, ticket stubs, gallery brochures and so on.

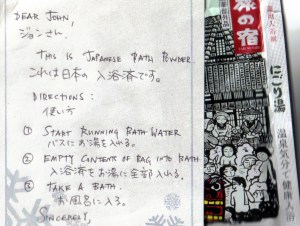

The envelope also held a packet of Japanese bath powder and charming handwritten instructions in English and Japanese for its use. This note went on my refrigerator door.

When I woke up last Friday morning and heard the news about the earthquake and tsunami, I immediately sent them an email. For all I knew, they could be in Japan.

I soon received a reply. He had flown out of Tokyo 24 hours before the quake hit. They were both safe at home. They hadn’t yet been able to contact family members in southern Japan, but early reports indicated the worst of the destruction had taken place on the other end of the country.

As I watched footage of the disaster (a noun worn too thin for an event of this magnitude, I think), my relief over my friends’ safety was tempered by the terrifying images that grew more unbelievable by the minute.

It will take years to rebuild Japan, and those who have lost loved ones or have been seriously injured will carry their pain and distress far into the future.

Stories of courage, good will and sacrifice are emerging, as they always do. We are at our best as human beings during such times. (Well, most of us are; there’s a special circle of hell reserved for those titans of political power who criminally mismanaged relief efforts during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, without question one of the most shameful episodes in American history.)

Why does it usually take a catastrophe to bring out the best in us? I’m reminded of a passage by Walker Percy from one of his non-fiction works, The Message in the Bottle (1975).

In this excerpt, Percy used the example of an alienated commuter, “partitioned” from reality by the dulling repetition of daily routine, to explore this mysterious phenomenon:

It is only in the event of a disaster, the wreck of the eight-fifteen, that one is enabled to discover his fellow commuter as a comrade; thus, the favorite scene of novels of good will in the city: the folks who discover each other and help each other when disaster strikes. (Do we have here a clue to the secret longing for the Bomb and the Last Days? Does the eschatological thrill conceal the inner prescience that it will take a major catastrophe to break the partition?)

These are excellent – if sobering – questions. As long as it continues to take train wrecks and earthquakes to jolt us out of what Percy called the “malaise” of modern consciousness, they will remain questions worth asking.

______________________________

John Hicks lives in Tuscumbia, Alabama.

Nice piece. I think you’re right about the word disaster. It literally means the “un-lining up of the stars” [dis+aster (astro)], which means “bad luck.” We need a stronger word.

Apocalyptic doesn´t work because it means “revelation” or “discovery.” Hopefully, governments will have a revelation and not put nuclear power plants on fault lines anymore. Just a thought.

Catastrophe is still pretty light because it implies a reversal of what is expected.

Holocaust comes closer to the images we’ve seen because it means “the burned whole.” And, cataclysm also fits because it refers to a deluge, flood or inundation.

So how about, “cataclysmic holocaust”? Now there’s an image that grabs you. It really suggests nuclear cloud darkened skies, atomic fallout, women, children and the elderly naked and half-burned to death, screaming in Edvard Munch-like horror.

Sorry… the aesthetics always run away with me. Maybe we should stick to “disaster” until it gets under control.

I’ve been thinking about those guys on the line trying to prevent meltdowns …

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-03-17/japan-churns-through-heroic-workers-hitting-radiation-limits-for-humans.html

It is amazing to see guys still working knowing that they will die from radiation sickness, many would have turned tail and run.